Supplied

SuppliedResearchers from the University of Alberta have found that a fossil assemblage of small dinosaurs in the Mongolian Gobi Desert indicates that dinosaurs may have been more social than previously thought.

Greg Funston, a U of A paleontology PhD candidate and Vanier Scholar, has found that Avimimus dinosaurs (beaked, metre-long, feathered dinosaurs that lived between 68 and 70 million years ago in the late-Cretaceous period), may have been social.

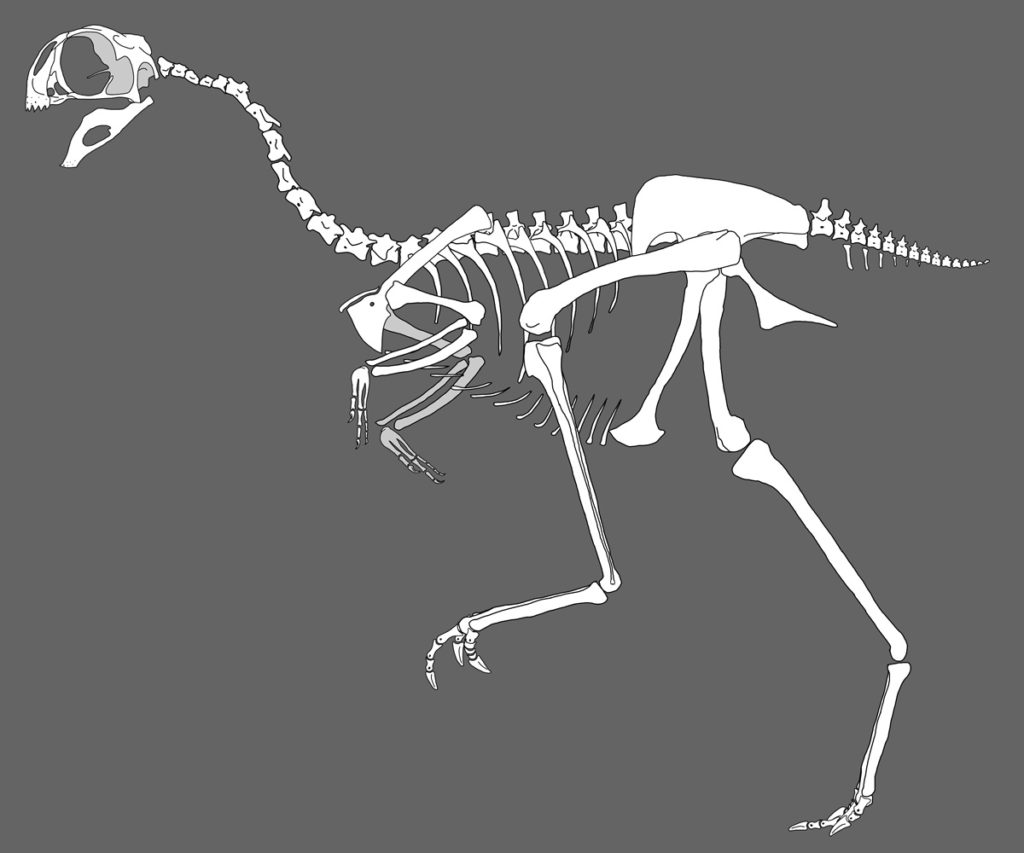

“It’s really weird in a lot of ways,” Funston said. “Its skeleton looks a lot like a bird. So that’s one of the most interesting features of the Avimimus.”

The excavation of these fossils began in 2006, when an Avimimus bonebed was discovered in the Nemegt formation of southern Mongolia. The project includes paleontologists from Mongolia, Japan, America, The United Kingdom, and Canada.

Funston said an important feature of the fossils is their quantity: 18. One of the implications of such a large group of fossils is that the Avimimus was social creature that may have fed in groups or participated in group mating behaviours.

“With a lot of dinosaurs right now, our perception is changing from lone wolf to things that are grouping together in, say a flock,” Funston said. “This is probably more akin to a flock of birds than it is to what we would imagine of dinosaurs going out hunting alone.”

The extent of the Avimumus’ sociality cannot be determined because they didn’t die where they were buried — Funston said they died and were transported by a river to their current location.

Even though these fossils were transported post mortem, Funston and his colleagues are still able to learn about how the Avivmimus lived, as most of the fossils he found were of adults. This composition could suggest mating patterns, for example.

“That is consistent with a mating group for instance,” he said. “In modern birds, especially sage grouse here in Alberta, you have these big assemblages where you’ll have up to a hundred individuals come together for mating displays, and the female will go through and choose which male she wants to mate with.”

Funston suggested that the Avimimus could have also fed as a flock, which is consistent with many modern animals.

Funston said one of the greatest challenges while working on the Avimimus site was fossil poaching. Poachers had left behind shards of bone where they had hacked away at the fossils in an attempt to find anything they could sell, he said.

“(One day) I visited about 25 to 30 sites and each of which had a skeleton, each of which had been poached,” Funston said. “In some areas of Mongolia, you have almost 100 per cent poaching of the sites, which really limits what we’re able to do scientifically.”

Today, paleontologists have to contend with samples being stolen in the form of fossil poaching, which is a worldwide phenomenon.

Fossil finds such as that the Avimimus give paleontologists insight into the social lives of dinosaurs, Funston said. He and his colleagues have now uncovered about a quarter of the Avimimus site and plan to continue searching for new samples in the area to learn more about how this dinosaur lived.

“The science is much more exciting than just big predators and huge, long-necked plant eaters,” Funston said. “There’s a lot more going on than I think most people appreciate.”