Supplied – Bruce Blaus

Supplied – Bruce BlausDiabetes researchers from the University of Alberta say they have discovered a biochemical pathway that could potentially treat — and even prevent — Type 2 diabetes.

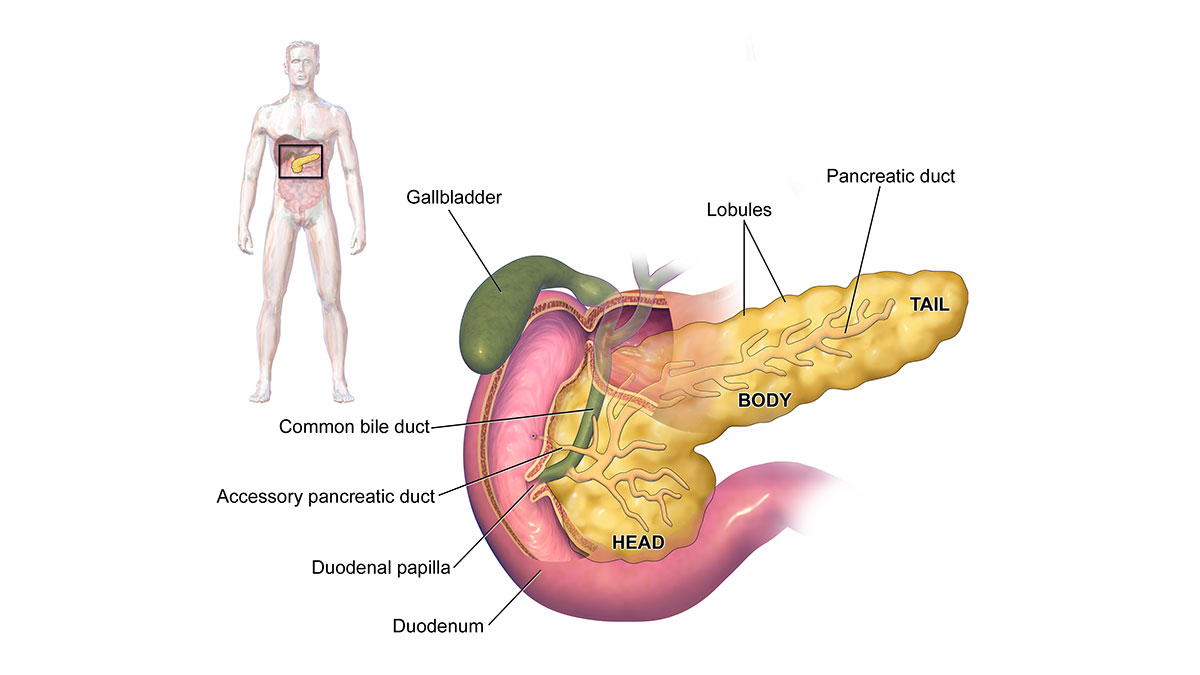

The team identified a molecular pathway that manages and controls how much insulin pancreas cells produce, operating much like a “dimmer switch.” This specific pathway appears to be absent in the pancreas cells of patients with Type 2 diabetes.

Patrick MacDonald, associate professor in the U of A’s Department of Pharmacology and lead researcher on this project, said it’s possible they could restore the function of this pathway by repairing islet cells in Type 2 diabetes patients.

“In normal people when blood sugar increases, their pancreas will make more insulin to store the extra sugar to overcome it,” MacDonald said. “But in Type 2 diabetes patients, their pancreas is failing and can’t make enough insulin. We’re trying to study the reason for the pancreas failing.”

Recent estimates from the Canadian Diabetes Association indicate that there are more than 10 million Canadians with diabetes or prediabetes. Those with diabetes can’t properly produce insulin when their body needs it.

MacDonald and his team started the research project five years ago and collected pancreatic cells from 100 organ donors with and without diabetes. He said Edmonton is “famous” for diabetic research where they have the expertise to found the project. The donated organs are not suitable for transplant, but proved “absolutely valuable.”

The whole research team holds a positive view about what would this pathway bring to us in the near future. There are no current drugs targeting the “dimmer switch” pathway, and the more MacDonald and his team learn about the pathway, the easier it will be to develop therapeutic treatments.

‘This finding answers the long-time mystery about how islet cells work and understanding this mechanism brings up potential treatment to Type 2 diabetes,” MacDonald said. “Both Type 1 and 2 diabetes studies have made dramatic progress in the past 15 to 20 years, and this discovery would definitely provide a solid foundation for future treatment development.”

But despite the recent medical breakthrough, MacDonald pointed out that researchers still have a long way to go in diabetes research.

‘We do all our experiments in the cell plates, which is in vitro studies. The tricky part is how we can apply such discovery into real people,” he said. “Now we have human cells from patients and non-patients so it’s really relevant, but we still have so much work to do.”