Alex Patterson

Alex PattersonGrowing up is more than turning 18. It’s more than moving out of mom and dad’s, starting university and having a credit card in your name. So what exactly does it mean to grow up, and what is the process that it entails?

The answer isn’t always clear, and the University of Alberta’s Nancy Galambos is a specialist in this field. Galambos, a developmental scientist and specialist in adolescence and the transition into adulthood, said the transition to university is a huge step towards independence because of the number of changes a student undergoes during this time. And not all of them will be ready to overcome these, she said.

“(Students) all of a sudden get a lot of freedom. What are they going to do?” Galambos said. “They have to make decisions about sex, substance use, how much to study … a student can get lost.”

Galambos started her research in adolescence, but as her research participants aged, she expanded her area into young adulthood and onward. Life stages are different in researching. Adolescent behaviour is a unique experience due to the heightened level of self-consciousness that’s typical of the group. Research involves questionnaires, surveys and interviews. Participants are asked a wide variety of questions relating to school, family, friends, substance use and sleep among many others. Questions are asked repeatedly in order to later show how people change over time.

As subjects move into new life stages, new questions must be added to account for new situations in life. Which is why the transition to university is so interesting to study, Galambos said.

“You can see people going off and changing directions in terms of what they want to do and how they see the world,” she said.

Participating university students begin as subjects in their first year and are tracked as they progress through academia. Some research is collected in daily questionnaires about students’ experiences, such as activities, feelings and sleep habits. Other studies collect data in monthly questionnaires, and participants are followed up annually after their first year. Along with these, academic data is sometimes collected from consenting students.

“We can try to connect their achievement and whether they drop out with their experiences in their first year of university,” she said.

The transition into adulthood is commonly assumed be chaotic. While young people tend to experiment with negative behaviours, they usually grow out of it, Galambos said. It’s called the “storm and stress” view, where people in the young adult age group are thought of as confused and troublesome. This is the most common misconception about the area of study.

“We have a tendency to look at young people and focus on all the problems, rather than look at them as out future citizens, and all that they have to contribute to the world,” she said.

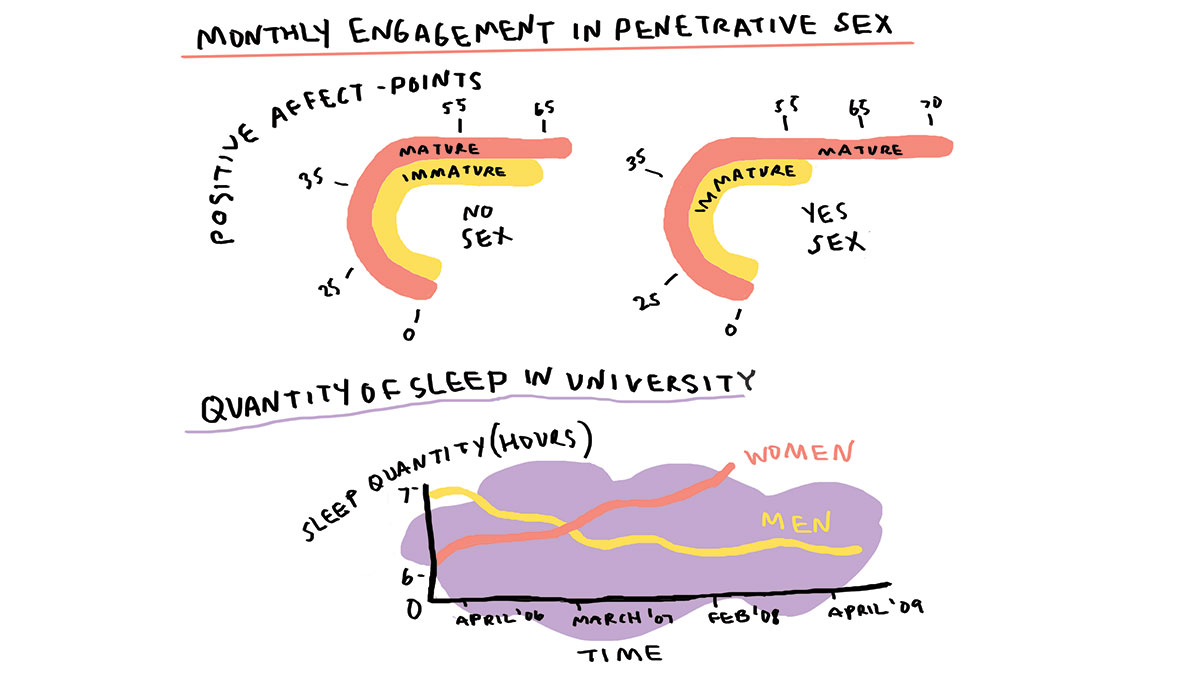

SEXUAL

Going to university opens students up to sexual freedom, which was limited for many in high school by the watchful eye of parents. Though it’s natural and normal to be sexually active during university, students vary in emotional maturity, which changes how they experience it, Galambos said.

“Some (students) might give into certain sexual activities when they don’t really want to, or they’re not ready,” she said. “Whereas others are psychologically ready.”

Galambos found mature students, who tended to be self-confident, independent and autonomous, felt good in months where they engaged in sex. Immature students, who were less self-confident, not quite independent and had a higher level of vulnerability, felt the opposite.

HEALTH

Leaving the context of home can lead to students developing unhealthy eating habits that can lead to eating disorders. A study by Galambos showed that female university students living out of home were three times more likely to show symptoms of binge eating than those who stayed home. They also were much more likely to binge-eat if they weren’t socially adjusted to university.

Galambos also found that students in their first year are vulnerable to sleep disturbances, and less sleep was often correlated with lower academic scores.

“All the temptations with (living out of home) can lead to less sleep, and less sleep is not good for academic performance,” Galambos said.

Another big influence of academic scores was alcohol. The more alcohol one consumes, the lower the grades, she said.

Mental health is also a concern in the university student population, and not just in first years either. Any study that measures amounts of depression in students comes up with large numbers, including studies specific to the U of A.

“It’s a big problem … surveys show that 40 to 50 per cent of university students are showing signs of depression,” Galambos said. “That’s really worrisome.”

SOCIAL

Developmentally, the young adult age group undergoes intense psychosocial development, especially during the first two years of university. Research has shown that students grow in their ability to be intimate — the broad sense of feeling connected to other people. For students that stay in university, the ability to connect socially improves over the course of their degree, especially in the first couple years. The reason for this is thought to be experience, Galambos said.

“University is a wonderful opportunity for a lot of students,” she said. “You’re increasingly becoming autonomous, you are able to meet new people in your courses. You can find yourself.”

Isolation is a common problem in students, especially for those in that transitional first year. This is largely because it accompanies all of the other stressors that come with being in a transitional state, Shauna Rosiechuk, Counseling and Clinical Services registered psychologist said. The feeling is common in those who have to deal with issues like learning to be independent, making new friends, working out long-distance relationships and really anything that comes with being in a completely new social scene, she said.

The burden of stressors is something that students, like fourth-year computing science student Rishi Barnwal, had to learn to overcome.

“I’ll be honest, first-year was one of the worst years of my life,” he said.

The negativity was strongest in his first semester. Living on campus helped in terms of academics, but it came with other challenges as well. For his whole life, Rishi’s parents had given him everything, which he didn’t realise until he had moved away.

“It left me feeling empty when my brother finally came and dropped me off at Lister,” he said.

Barnwal’s feeling of loneliness would leave while he was hanging out with his floormates, but after everyone retired for the night, the feeling would return. Another problem came into play if floormates didn’t get along. They couldn’t go home after school and have a break. It took a while to get over, Barnwal said.

Isolation — because it’s felt on an individual basis — is difficult to identify. People vary in how they experience and show when they’re feeling isolation and how they deal with it. Barnwal describes the feeing of being lonely as simply “nothing at all.”

“I think that’s the worst part,” he said. “You’re not happy or sad. You just feel empty, like something’s missing, but you won’t know what.”

Barnwal experienced a second hard-hitting wave of loneliness the summer after third-year. It was the summer when “literally nothing at all went right.” Barnwal was now living off-campus, nearly failed out of school, experienced a breakup, lost his job and had two of his pet birds pass away despite doing everything he could. His parents, who lived in Calgary, moved to Texas and his brother relocated to Los Angeles.

“In the span of a few months I pretty much lost everyone who ever loved me,” he said. “I realized how powerful this horrible feeling can be. It can basically make you lose interest to do anything.

Even Barnwal’s hobbies didn’t interest him anymore. What got him through was the support of a few friends kept in contact and made sure he was doing OK.

For those currently dealing with isolation, it’s important to note the main factor that allows the experience to become long-term is lack of action, Rosiechuk said.

“Loneliness is a passive state,” she said. “So it’s really maintained by letting it continue and not doing anything to change it.”

Barnwal, now in his fourth year, has many friends from different student groups and has since learned plenty of ways to deal with loneliness. He tries to understand when he feels lonely, and understands he has nothing to lose if he were to talk to people. His biggest regret in his first year was not doing this — talking to people and reaching out, he said.

“(People) don’t bite,” he said. “University is where you make the best friends in your life. They’re not always going to come to you.”

It’s important to differentiate between being loneliness and aloneness, Shauna Rosiechuk said. Loneliness is a feeling of sadness, while aloneness is the simple act of not being around others. In clinical psychology, someone feeling lonely may be asked questions to discover the source of anxiety or negativity about being alone. For some, the problem is being bored. For others, its sadness. Some even feel the existential anxiety of being alone in the universe, Rosiechuk said.

For Barhman, the difference is very clear — and one is definitely worse than the other.

“I like being alone sometimes,” he said.

Being alone can just mean taking a “me day,” which comes with many benefits the individual, such as giving time to reflect on life, but also just recharge. Barnwal’s most recent “me day” was relaxing. He read books, ordered a pizza and played videogames. To him, it didn’t feel lonely at all.

“Being lonely is a lot worse,” he said.

It’s always possible to be lonely, Barnwal said. It’s possible to feel loneley even if one has lots of friends, as the problem stems from not feeling connected to them. Nobody wants to experience loneliness, but there are times where it’s nice to be alone, he said.